When I began my formal cantorial training, one of the names that kept coming up was Moshe Ganchoff. Sure, there were others, Rosenblatt, Kusevitsky, Pinchik. But when teachers would mention Ganchoff’s name, it seemed to be in a different tone of voice. Subtle, but with just a slightly heightened sense of awe and respect. Ganchoff, the beautiful voice. Gachoff, the master interpreter of hazzanut. Ganchoff, the great improvisor. Yet, with all the platitudes awarded to Ganchoff, I remember hearing very few recordings of his singing. And as I began to build my record and CD collection of cantorial music, I did not come across any Ganchoff albums.

When I began my formal cantorial training, one of the names that kept coming up was Moshe Ganchoff. Sure, there were others, Rosenblatt, Kusevitsky, Pinchik. But when teachers would mention Ganchoff’s name, it seemed to be in a different tone of voice. Subtle, but with just a slightly heightened sense of awe and respect. Ganchoff, the beautiful voice. Gachoff, the master interpreter of hazzanut. Ganchoff, the great improvisor. Yet, with all the platitudes awarded to Ganchoff, I remember hearing very few recordings of his singing. And as I began to build my record and CD collection of cantorial music, I did not come across any Ganchoff albums.

Eili Eili

If you ask most people today about the song Eili Eili, they will likely think of the poem

Boris Tomashefsky

The opening line, “Eili Eili lama azavtani—My God, My God, why have you abandoned me” comes from the opening verse of Psalm 22 in which the psalmist cries out in anguish to God, yet concludes with an affirmation of his eternal faith in God. Similarly, in Eili Eili, which switches to Yiddish after its opening line, the protagonist sings of continued devotion to God and the Torah despite living through great despair and torment. Bracketing the narrative with Hebrew scripture, the song concludes with the words of the Sh’ma, whose inclusion presents a curious question about the plight of the song’s subject. Since the Sh’ma is the ultimate sign of a Jew’s faith, it could mirror the arc of the psalm, in which faith wins out in the end. However, the Sh’ma is also the final words a Jew traditionally recites before death, including martyrdom. Does the operetta’s character live despite tragedy, or perish on its account? Not to give away too much, I recommend hearing the whole work.

The true origin of the melody remains somewhat obscure. Though often credited to Sandler, he apparently never owned the copyright to the song and therefore never received any royalties. Sources indicate that there are many, including Rosenblatt, who claim that they had heard the melody in Europe as a folksong and that cantors of an earlier generation had used the melody in compositions for the selihot service.

Originally performed by a woman, Sophie Karp (formerly Sara Siegel Goldstein), it became associated with male singers when the great Yossele Rosenblatt added it to his repertoire. It has since been performed by many Jewish singers including Jan Pierce as well as non-Jewish artists such as Johnny Mathis, Perry Como, and even jazz vibraphonist, Lionel Hampton.

Ganchoff’s rendition is notable for its combination of operatic style, with Ganchoff’s bold and heroic voice, seamlessly infused with authentic cantorial nuances including krechts and beautiful hazzanic coloratura. And on the word “gekent,” Ganchoff subtly swallows the “nt” in a way that could only be described in the words of Jacky Mendelson, “Yum Yum Yum.” (For more on Jack-isms, see article on Jan Pierce from September 2016.) Beginning the opening Hebrew words in a slow triple meter, Ganchoff then sings the Yiddish lyrics which follow in a meter-free, davening-like fashion. At the climax of the piece, Ganchoff belts out the words “Adoshem Ehad—God is One,” seemingly effortlessly singing a high Ab resolving to a sustained G. Faith triumphant in the face of horror—all succinctly summed up in those two magnificently sung notes.

Ganchoff’s rendition is notable for its combination of operatic style, with Ganchoff’s bold and heroic voice, seamlessly infused with authentic cantorial nuances including krechts and beautiful hazzanic coloratura. And on the word “gekent,” Ganchoff subtly swallows the “nt” in a way that could only be described in the words of Jacky Mendelson, “Yum Yum Yum.” (For more on Jack-isms, see article on Jan Pierce from September 2016.) Beginning the opening Hebrew words in a slow triple meter, Ganchoff then sings the Yiddish lyrics which follow in a meter-free, davening-like fashion. At the climax of the piece, Ganchoff belts out the words “Adoshem Ehad—God is One,” seemingly effortlessly singing a high Ab resolving to a sustained G. Faith triumphant in the face of horror—all succinctly summed up in those two magnificently sung notes.

V’shamru

Next on Side A is V’shamru, set by the great composer of synagogue music, Zavel Zilberts, which Ganchoff sings masterfully. Ganchoff begins with a stately opening on the words “V’shamru v’nei Yisrael,” gradually building in intensity to a beautiful coloratura on the repeated “b’ris olam.”

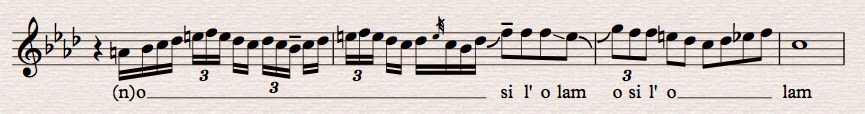

On the words “Beini uvein b’nei Yisrael os-hi l’olam,” Ganchoff first sings a modal motif, jumping the octave vacillating between the upper tonic and the b7 below, and then down and up on a controlled arpeggio on a minor 7th chord with lightly aspirated accents. Ganchoff repeats the words “Beini uvein,” elaborating on the upper ^8-^b7 motif adding the 9th above the octave twice and then the third time singing a major ^7, descending in the equivalent Ahava Raba mode.

He then sings two quick runs on “os-hi,” in Ukrainian Dorian reminiscent of the fast coloratura of Mordechai Herschman which my instructor, Hazzan Robert Kieval used to liken to a “machine gun.”

For “Ki sheishes yamim,” Ganshoff modulates to the relative major, throwing in a little text painting as he sings a high note on “shamayim.” Ganchoff returns to minor at “uvayom,” beginning the phrase in a somewhat subdued voice, a possible nod to God’s resting on the seventh day. On “shavas,” Ganchoff brings back the modal sounding ^9-^b7-^8 from before, and then repeating “uvayom hashvi’i shavas, Ganchoff reaches a Bb, his highest note on side A, before ending the piece with a half step cadence, ^b9-^8.

But these are all individual gems within a complete piece. Part of what makes it so great to listen to is Ganchoff’s apparent ease in producing this masterpiece. For me it’s reminiscent of watching a master soccer player dribble, juggle, pass, and shoot a ball as naturally as most people walk. Likewise, as though with the ease of engaging in casual conversation, Ganchoff delivers this marvelous rendition, summarizing Israel’s observance of Shabbat, modeled after God’s resting on the seventh day.

But these are all individual gems within a complete piece. Part of what makes it so great to listen to is Ganchoff’s apparent ease in producing this masterpiece. For me it’s reminiscent of watching a master soccer player dribble, juggle, pass, and shoot a ball as naturally as most people walk. Likewise, as though with the ease of engaging in casual conversation, Ganchoff delivers this marvelous rendition, summarizing Israel’s observance of Shabbat, modeled after God’s resting on the seventh day.

Kol Nidrei

Side B opens with Kol Nidrei. As with Eli Eli, Ganchoff artfully combines a heroic operatic style with distinct cantorial inflections. Unfortunately, while the performance is beautiful, it sounds a bit rushed, as if Ganchoff were pressed for time by an impatient patron. In fact, he may have been. In order to fit Kol Nidre onto a single side of a 45 album, along with another track, it may have been necessary to pick up the pace. Still, a very nice rendition.

Kidush

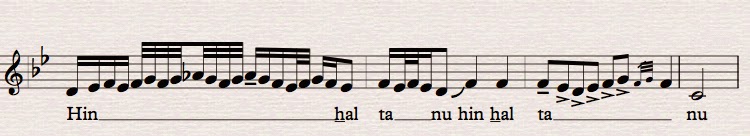

Ganchoff closes with Kidush for Friday night. There’s not much to say concerning Ganchoff’s singing on this track that I haven’t already noted. But one additional aspect of Ganchoff’s singing that struck me is his great flexibility when singing coloratura, particularly hazzanic runs, coupled with boldly intentional punctuation on other lines. Ganchoff displays both musical approaches in succession when singing the word “hinhaltanu” just before the closing b’rakha.

Don Gabor and Remington

While I wrote earlier that the record’s label doesn’t provide much more than that track names, it does offer some background into the album’s production. The label on the record reads in large black letters, set against gold squares “REMINGTON,” underneath which are the words in elegant script, “A Don Gabor Production.”

So what was Remington? And who was Don Gabor?

Born in Hungary in 1912, Donald Gabor moved with his family to America in 1938. He found work that year with RCA-Victor, first as a shipping clerk earning $12 a week, and within two years heading Victor's foreign records department.

Gabor would found his own company, Continental Records, with one of his first artists, none other than Hungarian composer Béla Bartók. In addition to classical music, Gabor produced several world folk records, successfully appealing to immigrants who, while enjoying the new American lifestyle, retained a taste for the music of their ethnic heritage.

In 1950, Gabor founded Remington Records, Inc, transferring many of the Continental recordings to LP and rereleasing many on the Remington Label. It would appear that the Ganchoff recordings reviewed here originated as two 78s (Eili, Eili with Kol Nidrei, and Kidush with Veshamru) on the Continental label before being released together on 45 on the Remington label.

To appeal to a multitude of demographics, Gabor created several labels—at least ten—the name of each geared towards connecting the music with a specific segment of the population. (Apparently, the same material was often released on multiple labels to successfully market individual releases to multiple demographics.)

To appeal to a multitude of demographics, Gabor created several labels—at least ten—the name of each geared towards connecting the music with a specific segment of the population. (Apparently, the same material was often released on multiple labels to successfully market individual releases to multiple demographics.)

Another appeal of Remington’s records was that they cost about a third less than those sold by the major labels. In order to sustain such low prices, it is said that Gabor did not sign top artists and used a cheap substitute for vinyl known as Websterlite. Though use of this material resulted in a poorer sound quality, it did not seem to impact sales negatively. One might draw a comparison to the success of the mp3 (not to mention youtube) as a medium for listening to music. Purists will tell you that the mp3 lacks the quality of other sound formats, yet most consumers neither know the difference nor care.

An additional factor in Gabor’s success with Remington was his hiring designer Alex Steinweiss who had previously designed records for Columbia Masterworks. Steinweiss created the REMINGTON logo and added in his own script (later patented as the “Steinweiss Scrawl”) the words A Don Gabor Production. Steinweiss’ design helped Remington records stand out among a sea of competition.

An additional factor in Gabor’s success with Remington was his hiring designer Alex Steinweiss who had previously designed records for Columbia Masterworks. Steinweiss created the REMINGTON logo and added in his own script (later patented as the “Steinweiss Scrawl”) the words A Don Gabor Production. Steinweiss’ design helped Remington records stand out among a sea of competition.

Working with Gabor at Remington was his cousin, George Curiss who in 1962 founded his own label, Tikva Records which boasted “the largest catalog of Jewish and Israeli as well as dance instructional recordings.”

Coda

So there you have it. Moshe Ganchoff on Remington Records.

Nu, after all this reading, you want I should let you hear a shtikle? You can listen to the recordings listed above—along with ten other tracks originally released on 78—on the FAU sound archive. Many other Ganchoff masterpieces are available here.

Nu, after all this reading, you want I should let you hear a shtikle? You can listen to the recordings listed above—along with ten other tracks originally released on 78—on the FAU sound archive. Many other Ganchoff masterpieces are available here.

Enjoy!